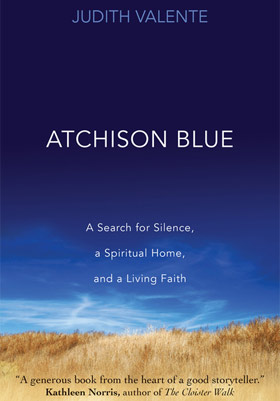

I reviewed this new book for The Engelwood Review of Books online edition. Judy Valente is a TV producer and poet whose life is changed when she begins visiting a Benedictine women’s monastery in Atchison, Kansas. I’ve found a lot of nurture with Benedictines myself, and it was fun to read and review this book.

An excerpt:

Valente keeps it real in Atchison Blue. She isn’t afraid to share her strong feelings. I liked to imagine I was reading a book called: An Angry Woman Goes To The Monastery. Because Valente is willing to reveal her emotions and mistakes she invites us more deeply into what Benedictine life can offer us. She shows us that practicing humility and conversatio can stretch us more than we ever imagined. Most authors I’ve read who write about Benedictine spirituality have a peaceful and poetic style. If they’ve had cathartic experiences with Benedictines they don’t write about them or they are artfully couched in literary language and kept at arm’s length. I admire Valente’s willingness to bring her full, quick-tempered self to the fore. She doesn’t hide behind stories about other people, as a journalist usually must. She’s unstintingly frank about the sins she brings to the Mount, how she is changed, and how she remains the same person. Conversatio, as Sister Thomasita says, “is the work of a lifetime” (110).

At its heart, this is a book about conversatio. Valente tries to wrap her mind around it variously through metaphors of a constant conversation, the growth and pruning of grapevines, the history of Atchison, Kansas, the blue stained glass windows, and the fragile, elderly sisters who live in the assisted living wing and yet who are rich, living examples of both pain and faithfulness. Conversatio is the discipline of ordinary life, no whether that life is lived inside or outside a monastery. It is a full commitment to being yourself, while striving to live beyond your limitations into who God created you to be, warts and all. Valente is harvesting grapes and a sister says, “The ripe ones are translucent; the light goes right through them.” Valente thinks, “I suppose you could say the same about the most spiritually mature people. They’re also the most transparent… unafraid to be who they are” (154).

Her own story is left unfinished, as it should be. Judith Valente puts it this way, “I wish I could say my visits to the Mount miraculously tamed my bad temper or healed my relationship with my stepdaughters. But that would not be conversatio. Conversatio isn’t a sudden tectonic shift. It is more like the steady etching of water on a shoreline. It is the work of everyday life” (174).

For the full review, click here.