Old houses have always seemed to me like chapter books of rooms: full of stories about the past, if you have time to read them. There were plenty to explore or “read” in the old Chicago neighborhood where I grew up.

The apartments and houses of my parents and friends had well-worn wood floors, carved stair-rails, built-in cupboards and bookcases, antique gas jets still in the wall (long shut off), maid’s rooms paired with tiny maid’s bathrooms, claw foot tubs, and cupboard-size doors on back porches once used by ice men to make deliveries. Our six-flat still had an antique intercom system (no longer usable) of one-inch brass tubes connecting each flat with the front door, so people could announce themselves by speaking in the tube.

You could imagine something about the lives of the people who’d lived there before.

Our suburban house was built in 1992, so all that looks historic here are the phone jacks.

Still, others lived here before we did: a few of their children’s tiny toys were left in corners when we moved in and their handwritten labels are still on the bins in the backyard shed. Every day, we see the paint colors, curtain rods, and bathroom fixtures they chose that we haven’t bothered to change. We can know a little something about them from what they left behind.

In the past, I’ve blogged about the farmland our subdivision was built on, and the man who watched his family farmhouse burned down as part of the construction process. I’ve blogged about the first European farmers who moved here, mostly from Vermont, in the 1830s.

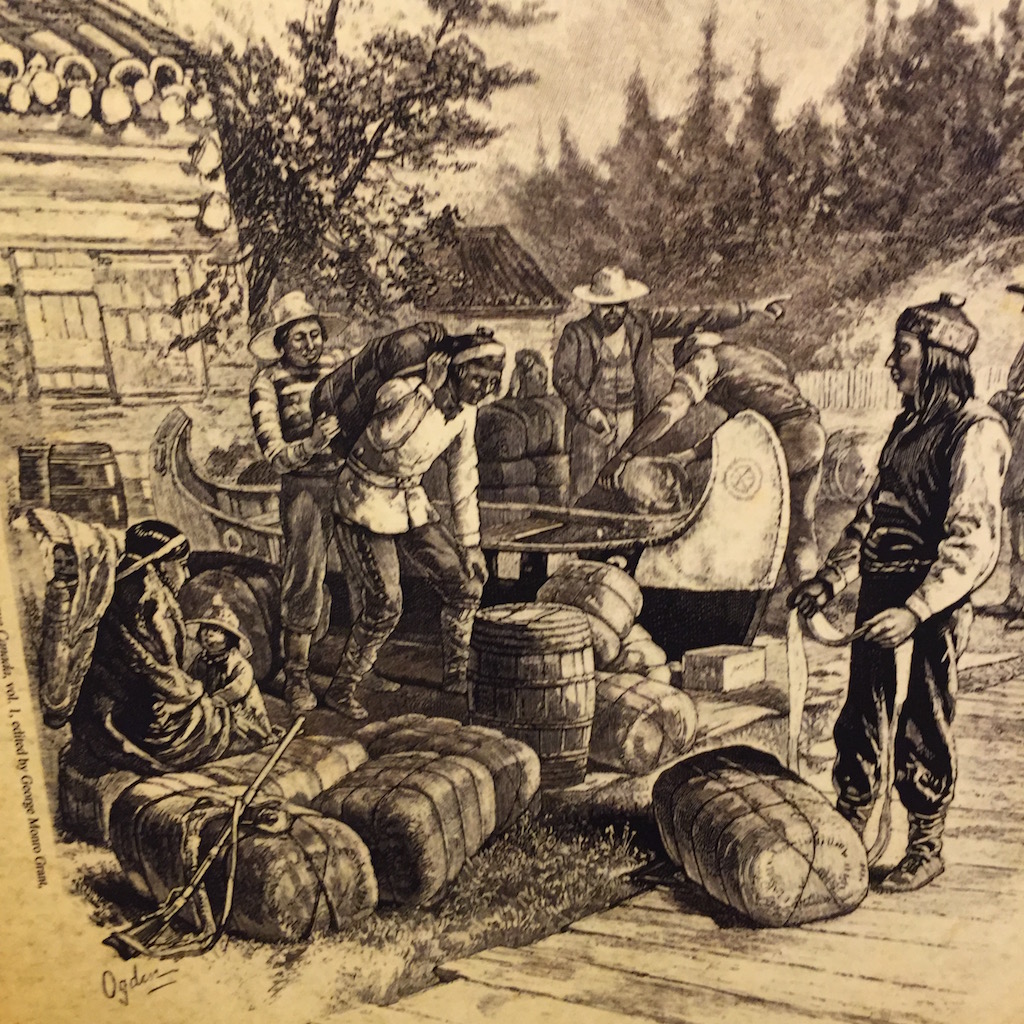

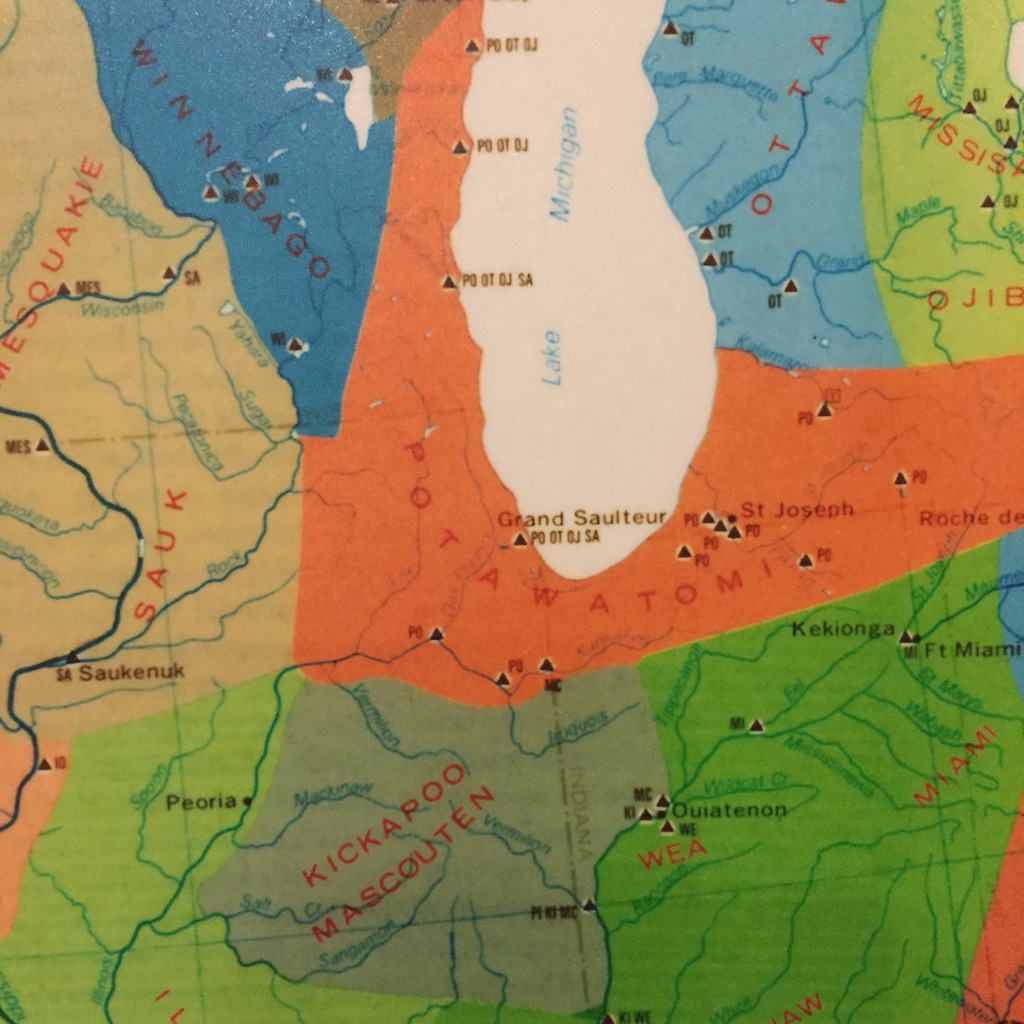

Before the Vermonters, French fur trappers were in this area for over two hundred years, and American Indians made their home on this land for generations. At the time of the fur trappers, it was the Potawatomi tribe (pot-tah-WAH-toh-mee). The tribe calls itself, Bodéwadmi, which means “People of the Place of Fire.”

There isn’t much left of this part of our history. There isn’t visible evidence in the landscape – physical or social – that the Potawatomi ever lived here. No ruins, no societies, no festivals, and few place names or street names – at least not in Bolingbrook. (There is a hockey team…)

In great part, this is because in the 1830s, all Illinois tribes — the Potawatomi, Illini, Sauk, Chippewa, Ottawa, and Fox – were expelled from the state. The federal government passed and enforced the Indian Removal Act, decreeing that all Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi were to move west of the Mississippi. Illinois tribes were moved to Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska. So, all people known to be Native American were exiled from Illinois. All of them.

We don’t have any Indian reservations or visible Native culture in our state for that reason.

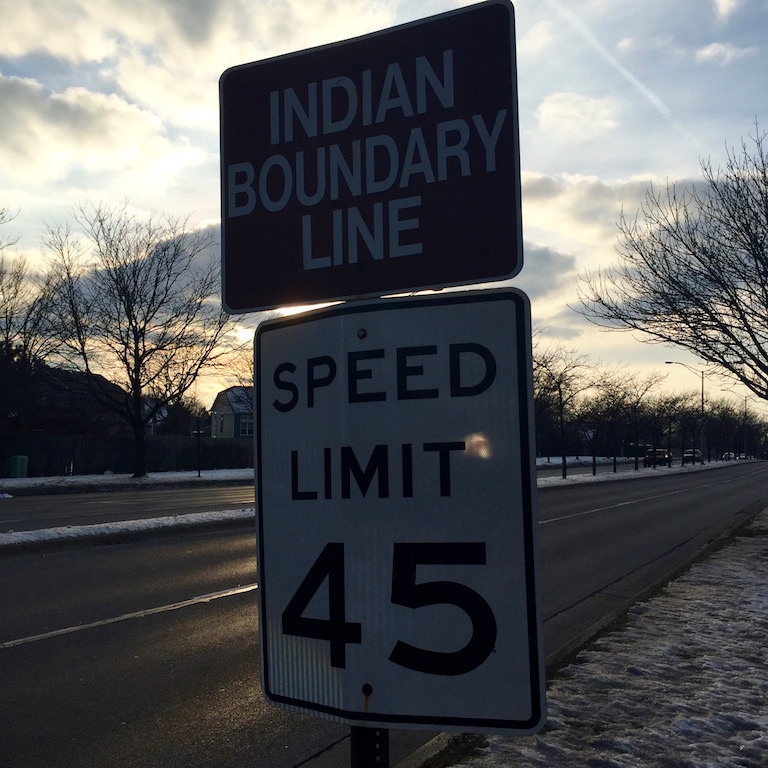

But we do have a lot of things here called “Indian Boundary.”

- Indian Boundary Line Park (all over the place)

- Indian Boundary Skate Park (Bolingbrook)

- Indian Boundary Line Road (Bolingbrook, Plainfield, Westmont, River Grove…)

- Indian Boundary YMCA (Downers Grove)

- Indian Boundary Golf Course (Chicago)

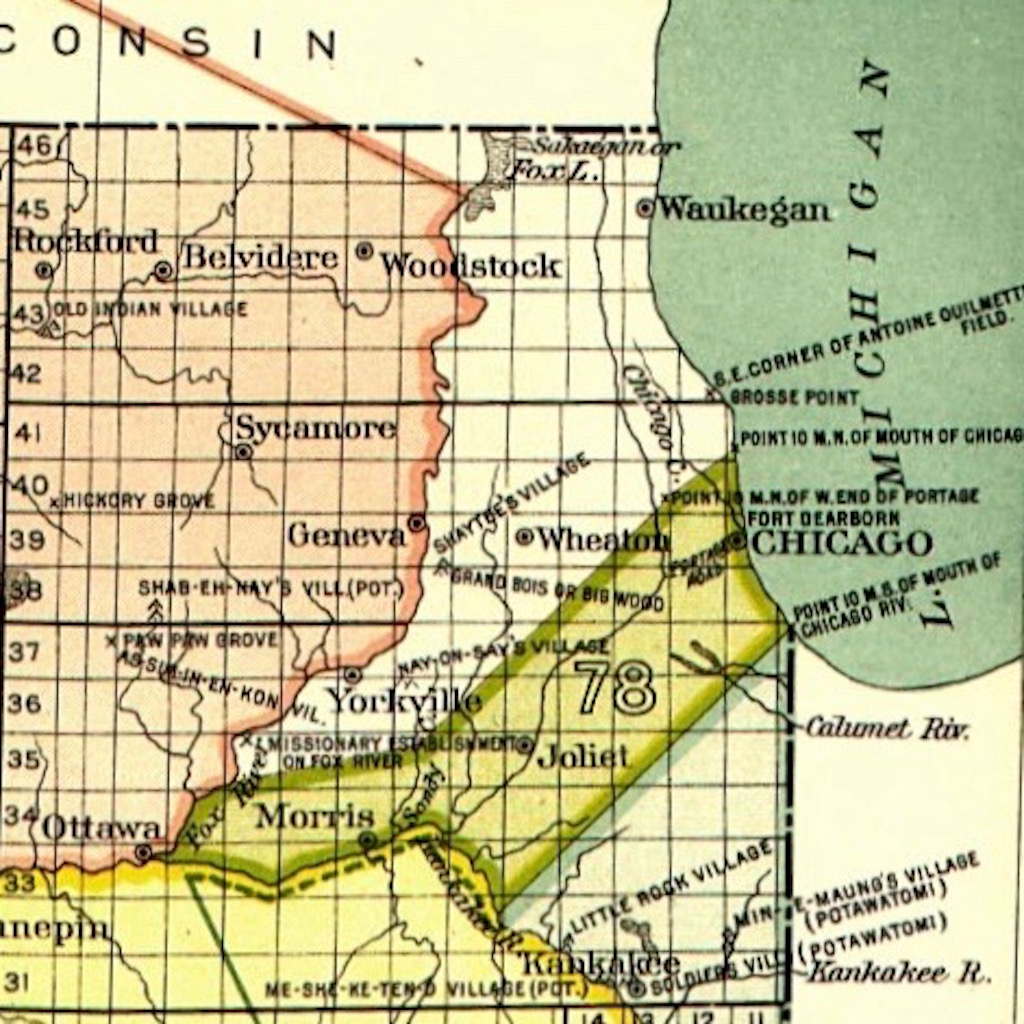

The Indian Boundary Line was established by the U.S. Government in 1816 as a safe passage corridor for trade, connecting Lake Michigan (Fort Dearborn) to the Kankakee River, via the Chicago and Des Plaines Rivers. It was “ceded” by the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi, in the midst of territory that the U.S. had recognized as theirs. As you can guess, that didn’t last long.

You can find signs (actual signs) around here that mark the presence of the Indian Boundary Line, but not the history or identity of the people.

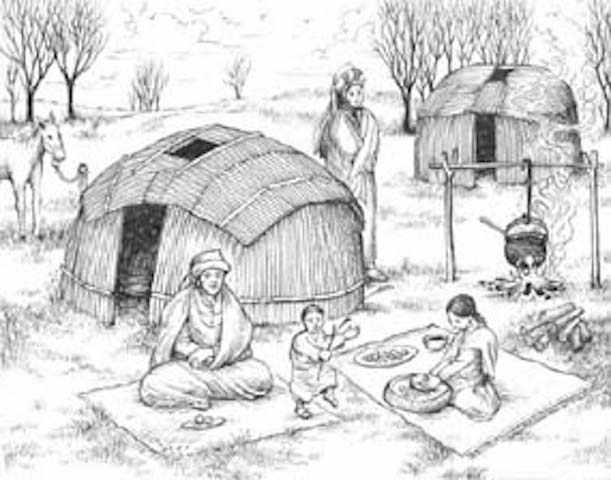

There’s a demonstration Potawatomi longhouse at the Isle a la Cache Museum in Romeoville, with the Lockport oil refinery looming in the background.

A longhouse, but no people – visibly, anyway. The Bodéwadmi community is now thousands of miles away, in Kansas and Oklahoma, with a few communities in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Cicero said, “Not to know what happened before one was born is to remain a child.”

Their history- unfair, tragic, and racist as it is – is part of the history of my house, my community, and my state. It’s almost certainly part of the story of your house and your community, if you live anywhere in North America.

It was our sociopolitical and economic institutions that forced these Indian tribes off this land. If we live here now, we have benefitted from their loss. We can’t change the past, but we can live with integrity and show remorse for how previous generations exploited American Indians. This land, in many ways, has a deep connection, history, botany, and identity that we might learn more about if we try to read more deeply into a history we mostly can’t see just on the surface of the landscape, here.

It is SO VERY SAD, and so often repeated throughout history, that white man decimated native cultures. Mostly it seems due to feeling superior and not through hardly any attempts to genuinely try and understand these original peoples….a loss for all in the end.